A University of Alabama professor’s latest online exhibition explores methods used by tobacco companies for years to target African Americans and other minority groups.

Dr. Alan Blum, UA professor and Gerald Leon Wallace, MD, Endowed Chair in Family Medicine, and his colleagues have spent the past three years working on “Of Mice and Menthol: The Targeting of African Americans by the Tobacco Industry.”

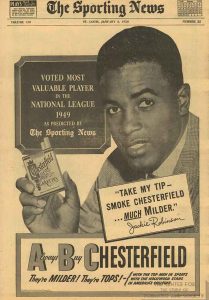

According to Blum, the themes of the exhibition reflect the categories he chose to collect beginning in the 1970s. He wanted to illustrate the targeting of African Americans through examples of both direct and indirect marketing: the overt cigarette advertisements in EBONY and other magazines on one hand, and the subtler sports and arts sponsorships on the other.

“From the outset of my medical activism as a resident in family medicine, I focused on the African American population, which was being disproportionately targeted by the tobacco industry,” said Blum. “I began monitoring and preserving cigarette advertising in the black press and attending and photodocumenting cultural events sponsored by the tobacco industry.”

In the mid-20th century, African Americans became a target of tobacco companies because studies showed they smoked less than their Caucasian counterparts.

“African Americans were an untapped market in the 1950s and were attractive because they were earning good incomes in post-war jobs,” said Dr. Robert G. Robinson, chair of the first chapter of the National Black Leadership Initiative on Cancer. “They were impoverished and buffeted by stress and the context of racism, thus making them vulnerable to the marketing strategies that associated cigarette smoking with wealth, sophistication and athletic prowess.”

Menthol cigarettes were particularly used in marketing campaigns. According to Blum, not a single advertisement for a non-menthol brand ever appeared in the leading African American magazine EBONY in its 70-year existence under its original publisher. The magazine also never produced a single article stating that cigarette smoking was the leading preventable cause of death among African Americans.

Through marketing campaigns from brands such as Brown & Williamson’s KOOL, Lorillard’s Newport and R.J. Reynolds’ Salem, African American men surpassed Caucasian men in cigarette smoking by the 1960s. The same trend was seen in women a decade later.

As the civil rights movement picked up steam, so did a push to end the targeting of African Americans by tobacco and alcohol companies.

According to Blum, a group of African American leaders in Detroit began pushing back against the proliferation of billboards for tobacco and alcohol in their neighborhoods in the mid-1980s. In 1990, the Uptown Coalition in Philadelphia was organized to prevent the marketing of cigarette brands targeted to African Americans.

At the same time, tobacco companies continued their decades-long tradition of sponsoring events at conferences of the NAACP and other civic organizations, as well as advertisements in the black press that saluted Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Congresswoman Barbara Jordan, South African President Nelson Mandela and other prominent figures.

“The exhibition doesn’t pull punches in looking at the lack of effort on the part of some health and civic organizations to reduce the impact of smoking on African Americans,” said Blum.

With the help of the Center’s collection coordinator Mary Clare Johnson, her predecessor Natalie Thompson and digital archivist and web designer Kevin Bailey, Blum’s exhibition took three years to produce. He is pleased that the exhibition is going to be used as a teaching tool in courses in health disparities, such as those taught by Dr. Angelia Paschal, interim chair of the department of health sciences in UA’s College of Human Environmental Sciences.

“The titration point when you realize the best artifacts and images have been selected, the various themes have come together, and the design looks intriguing and engaging is an extraordinarily satisfying feeling,” said Blum. “Another especially gratifying moment was receiving a note from Dr. Robinson praising the exhibition.”

Blum’s online exhibition can be found at https://csts.ua.edu/minorities/.