TUSCALOOSA, Ala. — Not surprisingly, vehicle crashes increased during the winter storm the last week of January in Alabama, but the iced roads shifted the risk of fatal crashes to rural roads away from the clogged roadways in the state’s urban metro areas, according to an analysis of crash data by researchers at The University of Alabama.

Using state crash data, researchers at the Center for Advanced Public Safety, or CAPS, compared the week of the winter storm, Jan. 25-31, 2014, with the same dates from January 2013. The winter storm that began Jan. 28 closed many schools and businesses through Jan. 31 because of iced roads that left scores of motorists stranded in high-traffic areas across central Alabama’s metro areas.

Despite less traffic in rural areas, crashes in those areas rose from 25 to 38 percent of all crashes comparing the last seven days of January 2013 to the week of the winter storm in 2014. It was a significant increase, according to CAPS researchers.

But fatal crashes in rural areas saw a much more significant increase during the week of the winter storm compared to the same week a year earlier. In 2013, that week saw four of the 14 fatal crashes, 29 percent, occur on rural roads. This year, 13 of the 16 fatal crashes, or 81 percent, in the state occurred on rural roads, according to the CAPS analysis.

Previous research at CAPS shows that for every 10 miles per hour above 40 mph, the chances double that a crash will result in a fatality. In some of the urbanized areas, it was almost impossible to attain a speed of 40 mph during the winter storm because of congestion. Also, the higher-volume roads tend to be the ones that get first sand or salt treatment.

“In the rural areas, the lighter traffic works against the motorist. Those who do not slow down – or were victims of those who did not slow down – clearly paid the price in increased severity,” said Dr. Allen Parrish, CAPS director and UA professor of computer science. “In particular, the rural Interstate highways showed an increase of over twice the number of crashes in 2014.”

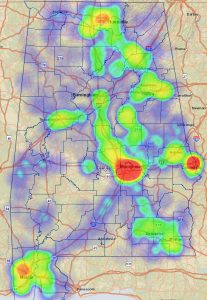

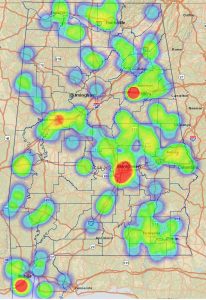

Plotting crashes during the week of the winter storm on a state map showed all types of crashes were more frequent in the places where they normally occur – the state’s population centers. For severe injury or fatal crashes, though, the plotted crashes show the dramatic shift of the more severe crashes from the urban areas where the traffic was most dense to the rural areas, where speed becomes much more of a factor.

Also, the move of severe crashes to rural areas meant single-vehicle accidents were more prevalent than normal. Single-vehicle crashes made up 37 percent of all crashes the week of the winter storm, about 9 percent more than expected. Similarly, crashes at intersections also accounted for 6 percent fewer of the overall crashes, according to the CAPS analysis.

Ambulance response time is also a factor in severity of crashes, especially in rural areas, and response times less than 10 minutes were down dramatically that week while response times between 11-30 minutes increased, according to the CAPS research.

Overall, crashes increased 40 percent during the last week of January this year compared to the same week a year earlier, but that increase came mostly from the lower severity crashes. Fatal crashes and crashes with severe injury combined for an 8 percent increase from 2013.

“This is not unusual in weather-related crashes in that most motorists have the training and common sense to slow down when the pavement gets slippery,” Parrish said. “In some cases around the urban areas, the traffic came to a standstill or was greatly impaired, forcing drivers to slow down.”

Tuesday, Jan. 28, 2014, the day snow and sleet iced roads while motorists were scrambling to get to shelter, saw 880 crashes, about three times the number of crashes from the same Tuesday in 2013. However, the following day, Wednesday, Jan. 29, 2014, had fewer crashes, 365, than the similar Wednesday in 2013 with 423 crashes, likely because people stayed off slippery roads and many roads were closed, according to CAPS.

Also, Wednesday, Jan. 30, 2013, was rainy through most of the state, which would account for that being the worst day of the 2013 week.

On the other hand, Thursday and Friday of the 2014 week were a bit worse for crashes than in 2013 as people returned to the roads, but the number of crashes on the Saturday of both weeks was practically the same, indicating a return to normalcy.

As for crash type, the proportion of rear-end crashes diminished by more than 6 percent, but the proportion of sideswipes increased significantly, both in the same and opposite directions. The increase in sideswipes on slippery surfaces typically results from sliding sideways into vehicles and objects.

The following tips on winter storm driving were provided by CAPS personnel:

- Do not become part of the problem in the first place, and do not get in the way of first responders. If at all possible, stay off the roads when they are slick with ice and snow. It is not your skill that is necessarily in question since you can be hit by another driver who may never have encountered these conditions.The result is the same.

- Sheltering in place until conditions improve is your best bet against any further damage or injury. Create an emergency plan that will keep you or your family safe until road conditions improve. Rarely are you safer in your vehicle.

- If caught in congested traffic, or your vehicle becomes disabled, do not continue to run the engine for the heater unless necessary; and then vent the vehicle adequately to eliminate possible buildup of carbon monoxide.This deadly gas has no smell and gives the impression that you are falling asleep.

- Keep necessary first aid equipment in the car as ambulance response times are slower in inclement winter weather. If you are involved in a crash with injuries, keep those who are injured covered and warm.

- If you have to drive, cut your speed to at least half of the speed limit, and recognize the dangers of down slopes and the inability to stop in some situations. Since your chances of hitting something is greatly increased, your only defense is to minimize the severity of the crash by reducing your speed, and, of course, always use your safety restraints.

- Don’t get annoyed by people who are passing you. Allow them to pass in the safest way possible, even if that means pulling over and coming to a near stop.

- Do not be deceived by rural roadways that appear to be clear of traffic. On wet ice, your vehicle will steer itself above a given speed regardless of how you turn the wheel. Wet ice is quite rare, and many people have never driven on it.

| Crash Severity | Jan. 25-31, 2013 | Jan. 25-31, 2014 |

| Fatal Crashes | 14 | 16 |

| Severe Injury | 251 | 270 |

| Possible Injury | 178 | 229 |

| Property Damage Only | 1,479 | 2,185 |

| TOTAL | 1,922 | 2,700 |

To keep the difference between weekday and weekend traffic from creating a complicating factor, the entire last seven days of January in 2013 and 2014 were used to make the comparisons. This takes into account the changes in traffic flow that might have resulted from the pre-storm warnings as well as the aftermath of the storm itself.

The study employed the Critical Analysis Reporting Environment, or CARE, a software analysis system developed by CAPS research and development personnel to automatically mine information from existing databases.

Try CARE online analysis at http://caps.ua.edu/online_analysis.aspx. Crash records for the study were provided by the Alabama Department of Public Safety.

The analysis was based on the most recently available data as of Feb.11.

Researchers at CAPS routinely provide a variety of safety studies and planning documents, such as Crash Facts Books and Highway Safety Plans.

In 1837, The University of Alabama became one of the first five universities in the nation to offer engineering classes. Today, UA’s fully accredited College of Engineering has nearly 4,500 students and more than 120 faculty. Students in the College have been named USA Today All-USA College Academic Team members, Goldwater, Hollings, Portz and Truman scholars.

Contact

Adam Jones, engineering public relations, 205/348-6444, acjones12@eng.ua.edu

Source

Rhonda Stricklin, associate director, analysis and outreach at the UA Center for Advanced Public Safety, 205/348-0991, rstricklin@cs.ua.edu