By Adam Jones

Photos by Matthew Wood

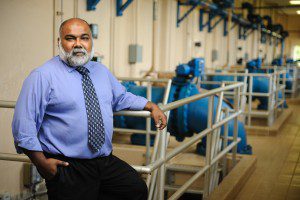

Once obsessed with mathematical perfection in solving complex problems, Dr. Andrew Ernest is convinced practical issues within complex systems, such as a municipal water system, can be solved by knowing just enough to fix the problem.

After all, this is how most problems within commonplace complex systems are tackled.

The United States tax code, for example, is a labyrinthine list of rules, but to fill out your taxes, you need only know about your finances. Experts — an accountant or tax software — ask us questions to complete the forms.

The human body and its interactions are still not fully understood, but to get a medical diagnosis and treatment, you only need to know your symptoms. Doctors – again, experts – ask us about ourselves to begin medical treatment.

Similarly, environmental management calls upon scientific knowledge, government regulations, economic factors and social science. However, managers of the public infrastructure need only know about the details of their issue. Ernest hopes specially designed computer programs can serve as the experts, guiding managers to solutions.

“It’s a process of discovery. In order for me to solve a problem, I don’t need to know everything I can possibly know, just what I need to know to solve the problem,” says Ernest, who directs UA’s Environmental Institute.

There are more than 50,000 water and waste-water treatment utilities in the nation, and ensuring they can withstand disaster, either natural or man-made, and get back to full operation is critically important.

“The entire economy of the United States can be brought down by tampering with the water system,” Ernest says.

Like Turbo Tax for water systems

To support water resource operators, engineers and managers in protecting and recovering their systems, Ernest built a decision-support system, a computer program that exists in the cloud, resting on a server and accessed on computers or mobile devices. The decision-support system could streamline current processes that often call upon managers to hire consultants to troubleshoot or sift through reams of data and regulations themselves to reach a solution.

“The decision-support system is comprehensive, combining mathematical models with tacit knowledge,” Ernest says. “It has a coherent interface for the end user to get useful information.”

Math models can be too rigid to account for real-world decisions, Ernest says. The decision-support system includes an inference engine that combines the math model with a sort of rule-of-thumb decision-making process gathered from actual experts. Through a series of questions, the system tells water operators what they need to know based on their answers. In a way, it’s like Turbo Tax for water systems.

For now, Ernest has applied the decision-support system to three software tools he calls Water Wizards. The first, Decon Wizard, can provide engineers, managers and operators with recommendations for decontaminating water distribution networks.

“At the local level, public water distribution system operators and decision makers need some way to determine what part of their system will be adversely affected, the extent of the impact, and the decontamination procedures that would need to be executed,” Ernest says. “The inference engine will process this for them.”

By answering questions posed by the software, water managers could quickly devise a plan of action specific to their problem, saving precious time to restoring service.

The decontamination tool is meant to help recover from a disaster, but Ernest has devised tools to help plan and respond to a disaster. After all, few water and wastewater systems in the country can afford to strengthen every pipe and lay redundant pipes and systems, he says.

Minimize the impact

“You have to accept that you can’t prevent malicious acts or a natural disaster, but what you can do is minimize the impact,” Ernest says.

And lessening the impact of a lack of clean water includes assessing the economic consequences of disruptions in water service. Ernest designed software that can investigate the impacts on local and regional economies resulting from both water service disruptions and subsequent recovery actions. It should assist water utility operators, as well as local and state governments, in making more informed resource allocation decisions after a disruptive event.

The second, Econ Wizard, predicts the money loss for any or all sections of the system so governments can be prepared for the worst, and, more importantly, help them devise strategies to minimize the impact.

“A water utility is part of regional economic development,” Ernest says. “If it goes offline, the local economy can take an immediate and sudden shift, so managers need to know the priority in restoring service. This is a predictive tool that can lay out the road to recovery.”

Another planning tool, WDS Wizard, is designed to provide context-sensitive recommendations for optimizing network operations or the best way for the system to operate that lessens the impact for a disaster. When used with the economic planning tool, water systems can decide which parts of the system need redundancy – such as the parts that service a hospital or a small town’s biggest employer – and develop additional plans, such as the positioning of water tanker trucks in areas unlikely to be restored quickly.

“Typically, water board directors are not trained enough to make these decisions,” Ernest says. “We can tell directors the value of water for their area, so they can plan accordingly.”

Applicable to flood preparation

To get these Water Wizards to operators, Ernest and UA are spinning off a company called Open Environment that could service utilities.

“The whole idea behind this is not to make a lot of money, but a private company is created to be more nimble in handling the technology in the private sector,” he says.

The software tools would likely be appealing to smaller systems since large utilities have the ability for in-house expertise and services are already catered to their needs, Ernest says.

Ernest is expanding the applications of the inference engine technology into other areas with complex systems and rules. The agriculture industry could use the technology to prepare and respond to environmental issues at a farm, for instance.

The technology could be applied to flood preparation and response, and Ernest is in the early stages of working with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to create a flood tool that can translate rainfall amounts, specific location data and water flow maps into responder action plans and decisions.

Dr. Ernest is a UA professor of civil, construction and environmental engineering. This work is funded by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security through the National Institute for Hometown Security.