By Chris Bryant

Photos by Bryan Hester

A chronic pain condition and numerous gastrointestinal disorders may all be caused by a virus.

That’s a Tuscaloosa-based surgeon’s theory likely headed for a clinical trial early next year and one drawing support from a University of Alabama researcher who studies how viruses replicate.

The theory of Dr. William “Skip” Pridgen, the physician, is now at the core of a start-up company, Innovative Med Concepts, which has already raised most of the capital needed to fund the Phase II clinical trial to test a novel pain-treatment therapy.

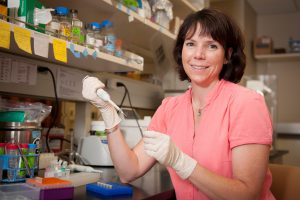

Pridgen is the company’s president and managing partner. Dr. Carol Duffy, a UA assistant professor of biological sciences, serves as the company’s chief scientific adviser.

The clinical trial will test the effectiveness of a combination of two drugs in treating fibromyalgia, the chronic pain condition known both as a diagnostic and therapeutic dilemma. The trial, pending FDA approval, will involve 140 fibromyalgia patients at 10 sites around the country.

Results from lab work performed by Duffy could further support trial results and also lead to a potential diagnostic tool for physicians treating patients who exhibit fibromyalgia symptoms.

Once FDA authorization is granted and remaining funds are secured, the trial would be operated by a contracted clinical research organization. The researchers hope it will begin by February 2013.

“We are now in the final stages of accumulating investors,” Pridgen says.

Proceeds from the sale of the company’s recently launched smartphone app, called U Shape Health, will also help advance the research. The app was designed by Pridgen to encourage healthy lifestyle choices among its users, and it was launched with chronic-pain sufferers in mind.

The unnamed medicines have previously shown to be effective in treating the virus at the center of Pridgen’s theory. He earlier filed a provisional patent on the repurposing of both of these drugs for the treatment of fibromyalgia and various gastrointestinal disorders, as they had not previously been known as treatment options for those conditions.

The company is assisted by an experienced team of consultants and UA’s Office for Technology Transfer.

Most physicians treat, and understandably so, according to their training, Duffy says, and so she said she was surprised to see Pridgen, a surgeon, exploring non-surgical options to help his patients.

“Most of the time,” Duffy says, “if you’ve got chronic pain and you go to a pain doctor, they are going to put you on narcotics; you go to a psychiatrist, they are going to put you on anti-depressants; you go to a surgeon, they are going to want to cut. But,” she recalls telling Pridgen, “‘here you are, a surgeon, putting people on anti-virals.’

“I was impressed that he was willing to go the extra mile and take this on.”

Duffy, on the other hand, is a molecular virologist and laughs heartily when asked what she would have thought had someone asked her two years ago about the likelihood of working with a physician to raise funds for an upcoming clinical trial.

How the two met ties back, as do most things affiliated with The University of Alabama, to a student.

UA pre-med student Jasmina Hira was shadowing Pridgen in his treatment of patients. The surgeon told the student of his theory and she, having been in one of Duffy’s recent classes and knowing her interest in all things viral, asked if he was familiar with the UA faculty member. She encouraged Pridgen to contact Duffy. He did. And, soon, a partnership developed.

Pridgen, who has treated more than 3,000 patients with chronic gastrointestinal issues and, more recently, chronic pain, says his theory began developing after seeing periodic recurrences of many of his patients’ discomforts.

He theorized there was some type of persistent infectious agent present. They would be fine for periods, and then they would experience stress, and their problems would recur. As the patients aged, the duration of their flare-ups was longer, and the time period in between flare-ups was shorter.

They were getting sicker.

Pridgen theorized it might be a virus, so he prescribed an anti-viral drug for their treatment. His patients responded positively. Because some of them also voiced other complaints, he also prescribed a second medicine, which also happened to possess anti-viral properties.

Upon those patients’ return, they indicated that not only were their GI problems much better, but other problems, including chronic fatigue, fibromyalgia, depression and anxiety were improving, and that their energy levels were rising.

In an observational study of some of Pridgen’s patients, he found the medicine combination had an efficacy rate of almost 90 percent.

Duffy explains how it is that viral infections can so easily recur and how this adds further credence to Pridgen’s theory.

Most people, when they’re children, become infected by these viruses, Duffy says. The virus particles travel up the nerves to a ganglion, a mass of nerve cells.

“The viral DNA just sits there the rest of your life,” Duffy says. Stress or, for women, even hormonal changes, can cause the virus to re-activate, travel back down a nerve branch and result in more inflammation.

“There are a lot of places in the body where this virus can hang out, and one of them is in the gut,” Duffy says.

The two medicines to be tested within the clinical trial work in different ways to counter viruses, Duffy says.

“The first drug inhibits the virus from replicating at one stage of the virus life cycle, while the other drug inhibits it at another stage and, in addition to that, it also inhibits the virus from reactivating. So, you are basically hitting this virus in three different ways.”

The UA professor’s role in the effort comes in two waves. First, she is seeking to confirm the virus’ presence in the affected patients. As part of his diagnostic process for patients presenting with both fibromyalgia and chronic GI disorders, Pridgen will take a tissue biopsy. Part of this biopsy will be sent to pathology for analysis, and part will be sent to Duffy’s UA lab.

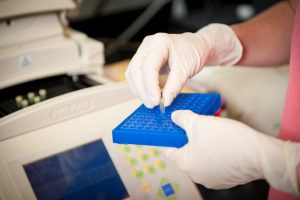

Using a technique known as PCR, Duffy will make enough copies of the tissue’s viral DNA, a process known as amplification, to sequence the virus. By sequencing it, the researcher can identify whether a virus is present, and if so, determine precisely which one it is.

The second aspect involves the potential development of a quantitative test to determine whether a person has fibromyalgia. Presently, such diagnoses are based on patients’ subjective responses to physicians’ questions about their pain.

In potentially developing such a test, Duffy is focusing on signaling molecules in the body called cytokines. The body produces different levels and types of cytokines based on what it encounters, Duffy says. It typically deals with encountered bacteria relatively specifically, turning on particular countermeasures to combat different bacteria.

Viruses, on the other hand, are “stealthy, and they evolve pretty fast,” Duffy says. “Our body’s way of dealing with a virus is basically just to turn on everything. The analogy has been made of trying to kill a mosquito with a machete.”

And all of that machete swinging causes problems.

“You look at the cytokine levels of patients who have fibromyalgia, all of their pro-inflammatory cytokines are elevated, and their anti-inflammatory cytokines are way down,” Duffy says. “So, the body is not regulating itself right.

“It’s basically exaggerating its reaction to the virus. Any little stress reactivates the virus, and, rather than the body saying, ‘Oh, this is just a virus, I’ve been living with this since I was five,’ the body keeps saying, ‘Oh, my God,’ and throws on all this inflammation, and that gives these people this pain.

“There is a theory that all pain, one way or another, is inflammation,” Duffy says. “It’s inflammation gone awry.”

Duffy will obtain blood samples from the clinical trial participants and measure cytokine levels. Participants will periodically rate their pain levels during the course of the trial, and Duffy will study whether there is a correlation between the patients’ reported pain levels and the cytokine levels.

If a correlation is shown, Duffy would then check cytokine levels in healthy people to gauge the typical difference in cytokine levels between pain-free people and people experiencing pain. This could lead to potentially pinpointing a cytokine level where fibromyalgia treatment would be acceptable.

Chronic pain and fibromyalgia are just two of a number of other chronic conditions that may be made better by this combination therapy, the researchers say. Fibromyalgia is the most severe condition, so it was selected as the first condition to be studied.

If the clinical trial and tissue study prove Pridgen’s theory correct, Innovative Med Concepts would then potentially approach pharmaceutical companies to gauge their interest in buying the patent and making the drugs available for fibromyalgia and a number of other conditions.

For someone whose career thus far has been devoted to basic research, Duffy says this new venture has required a shift in her mindset, and she said she finds it rewarding to potentially more directly help the public through her research.

“Everything I’ve ever done has been on grant funding, and grants are funded with taxpayer dollars,” Duffy says. “Yes, I do my best to give them value for what they are giving me out of their taxes – by doing good research, solid research and by being a careful scientist. Even with basic research, someday someone is going to be able to use it for someone’s benefit. With this, though, you can help people in a much more direct way.

“For somebody who is a molecular virologist — whose research program is based on ‘how does this virus replicate?’– to have the opportunity to do something like this is very rare and very exciting.”

Pridgen concurs.

“We may have found a rather big piece of the puzzle that no one has been able to figure out,” Pridgen says. “It’s an exciting time for me, Carol and The University of Alabama.”