Editor’s Note: Hough plans to attend UA’s commencement ceremonies at Coleman Coliseum beginning at 9 a.m. on Saturday, May 5. Although she’s a member of the MBA class that will receive degrees in the 1:30 p.m. ceremony, she is attending the morning ceremony as a guest of a graduate.

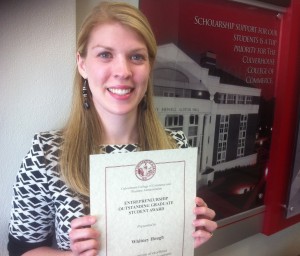

TUSCALOOSA, Ala. — Dr. Whitney Hough is scheduled to earn her MBA from The University of Alabama this week, but she’s not looking forward to joining the business world.

She’s already there.

If all this smells a little fishy, you don’t know the half of it.

Hough is a research engineer in a start-up company called 525 Solutions, an operation incubating on the UA campus. Walk into the company’s laboratory within UA’s Alabama Innovation and Mentoring of Entrepreneurs, or AIME building, and you’re struck by the distinct smell of shrimp.

But, Hough, who holds a doctorate and two additional chemistry degrees from UA, and her company colleagues aren’t in the restaurant business. They are removing a naturally occurring compound from shrimp shells and using it in developing a new type of bandage – one that contains anti-bacterial properties along with vitamins and minerals to promote healing.

The product, Hough says, could be particularly helpful for those with diabetic ulcers.

“Diabetic ulcers result in 100,000 amputations a year,” says Hough, 28, and an Albertville native. About half of those losing a limb from a diabetic ulcer lose their life within five years, she says.

The company’s CEO is Dr. Gabriela Gurau, a post-doctoral researcher at UA. Also assisting the company, under a sponsored research agreement, is Leah Block, a first-year chemistry graduate student.

After analyzing different types of wound dressings presently on the market for diabetic ulcers, UA researchers believed they could develop a better one. The constricted blood flow to diabetics’ extremities makes skin injuries particularly problematic, Hough says. This decreased blood flow means fewer nutrients reach the injury and the body has a difficult time repairing itself.

As a result, a relatively minor injury on a diabetic can become easily infected and a deep diabetic ulcer can develop. A moist dressing, one that behaves more like the body’s skin, is needed to combat the problem, Hough says.

One of the keys to the new bandage is something called chitin. Chitin, Hough says, is the material that provides a shrimp shell with its texture. In other words, it’s what makes you want to spit out a piece of shell if you accidentally get some in your mouth while trying to enjoy the delicacy underneath.

“We want to pull that out,” Hough says of the chitin, “because that compound is naturally anti-bacterial. It fends off infections and provides a nice way for the wound to heal.”

Extracting the chitin, in a pure form, from the shell had previously proven difficult. But UA researchers discovered a way to use a relatively new class of solvents, called ionic liquids, to do the job. Ionic liquids are liquid salts which have other unique and desirable properties that traditional solvents do not.

525 Solutions won a $150,000 NSF Small Business Innovation Research Fund, based on the discovery, to further develop the bandage and potentially bring it to market. Dr. Robin D. Rogers, holder of the Robert Ramsay Chair of Chemistry at UA, is recognized as a world leader in the use of ionic liquids and is an owner/founder of 525. If successful, the bandage project will spin out into a new subsidiary company, ILChiTec, with Hough, Gurau and Block as primary owners.

It was this grant, Hough says, that helped make it possible for the company to hire her in January.

Another ocean organism, seaweed, plays a role in the UA bandage-development process. The researchers combine the chitin with a compound called alginate, present in seaweed, to produce a fiber that would later be woven into a bandage. The alginate exists in a gel-like state, Hough says, which provides the fiber with moisture needed for a diabetic wound bandage.

“Our technology works to mix those two polymers together into a fiber that has both a gel-property and an anti-bacterial one. We also are working to infuse minerals and vitamins into the fibers so that when it comes into contact with the wound it would help promote cellular growth and help to close the wound faster.”

The researchers are working to perfect the precise mixture of ingredients before moving ahead with further testing. Working through both AIME and UA’s Office for Technology Transfer, the company hopes to later license the technology to others who would manufacture the bandages.

The scientists continue seeking answers to challenging questions that arise in the research, but one thing is evident. Considering the distinct odor that surrounds her workdays, Hough seems certain that one particular entrée will not be a part of any post-commencement dinner plans.

“I don’t think I’ll ever want to eat shrimp again.”

Contact

Chris Bryant, UA media relations, 205/348-8323, cbryant@ur.ua.edu

Source

Dr. Whitney Hough, 256/506-4888, hough001@crimson.ua.edu; Dr. Gabriela Gurau, 205/239-0892, gurau001@as.ua.edu; Dr. Robin Rogers, 205/886-4312, rdrogers@as.ua.edu; Dr. Dan Daly, director of AIME, 205/348-3502, dandaly@ua.edu; Dr. Richard Swatloski, interim director, Office for Technology Transfer, 205/348-8583, rpswatloski@ua.edu