By helping youth understand the science behind their own troubling behaviors researchers seek to improve it

By David Miller

Photos by Jeff Hanson

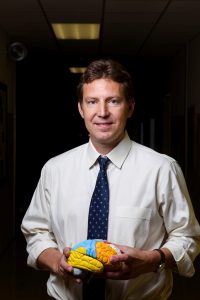

Dr. Randy Salekin makes his way through a bare hallway, his briefcase, laptop computer and EEG neuro cap in tow.

He’s about to interact with a group of people who have a variety of behavioral issues: substance abuse, conduct disorder, criminal mischief and gang activity, among others. They’re in a state-managed correctional facility. Some will be there as few as three months. Others will have a two-year stay.

Salekin sits, boots up his computer and begins demonstrating the different parts of the brain that are related to impulsive and unsympathetic behaviors.

Soon, the participants begin asking “why?”

They’re children, naturally inquisitive and often blunt. But for the boys at the Alabama Department of Youth Services Vacca Campus in Birmingham, they’re intrigued by the science behind their own behaviors.

“The kids realize they have, essentially, hardware and software that you’re trying to change, and they’re part of that process,” says Salekin, a professor of psychology at The University of Alabama. “It takes a lot off them, as far as the blame and responsibility that they’d, traditionally, have.”

Salekin and his team of graduate research assistants have developed a system that combines science education, technology and positive psychology, as well as positive reinforcement, that he says has been more effective at reaching troubled youth at the facility than typical methods, like empathy training or strict discipline.

The UA-led team has conducted the interventions at DYS with boys ranging from ages 12 to 18 since 2012.

Their first approach is to pique the children’s interest in learning about their brains and brain functioning. This lessens the initial focus on what they’re doing wrong and why they shouldn’t repeat the behaviors.

Instead, the emphasis is on scientifically explaining the mechanics of the brain that led to them acting impulsively and, perhaps uncaringly, toward others.

Salekin uses his laptop computer and LCD player to explain brain plasticity and how the youth can help regulate emotions, and show greater empathy toward others, while their brains continue developing.

The children are then tasked to develop a five-component plan aimed at improving relationships with friends and loved ones. Other plans target education, careers and athletics, but the common thread is “improvement.”

“It allows them to think about how they’re in control of some of the things they do, and ‘what would happen if I use these skills,’” says Melanie Hunter, DYS case manager. “It’s about getting them to understand they have the power to do it.

“I’m just a vehicle. We have kids who have mental health and behavioral issues, and, in the past, they’ve relied on medications, but most of it has to do with their willingness to change.”

Salekin said previous studies of positive interventions have mostly been applied to participants who are adults, college students or depressed patients. None, at least at the point when he began working with DYS, used the approach with both large- and small-group interventions for children having callous-unemotional traits or conduct disorder.

Further, any previous positive interventions with children focused on well-being rather than correcting behavior.

The novel approach has yielded positive data on multiple fronts, Salekin says.

“Improvements have been made in the behavior of youth on the units,” Salekin says. Also, behavioral measures (via self-reports), which include gauging developmental maturity, amenability to treatment, risk, and arrogant, callous, and daring impulsive traits improved.

“We are seeing some improvement in behavior and declines in traits such as daringness that are more harmful to the young individuals. These are very positive markers for us.”

While Salekin and his team identified positive results, they’re analyzing the progress by groups. Individual markers are more difficult to identify, particularly when the children leave the facility.

Recidivism rates are difficult to collect — especially when youth move. The data for behavior with friends and loved ones and the children’s motivation to set goals and work toward them can’t be tracked once they leave.

The researchers say they get a sense of the direction in which the child is heading based off their participation levels during interventions.

“The kids who are buying in are the ones who have a lot to contribute during our group session,” says Abby Clark, one of Salekin’s graduate research assistants. “You can tell that they’re really thinking, processing it and applying it.”

“For me, it’s been case by case. At some point, there are kids we know we are helping, but we’re sending them back home to sometimes chaotic situations. That is tough. I’ve had moments of leaving work, thinking about it, and being a bit discouraged. You hope that you’re planting seeds for change in the future.”

There’s physiological data, too. It’s rooted to the tasks the researchers assign the students — like creating and actively pursuing goals. This, the researchers say, affects brain development so it can be regulated. The idea is to stimulate different parts of the brain during a child’s natural development and to measure the growth using an electroencephalogram, or EEG, which assesses electrical activity in the brain.

“With kids who have particular disorders, we’ve found they have a longer latency to new stimuli,” Salekin says. “After treatment, the latency appears to be shorter and the general amplitude is lower, suggesting that there may be a quicker response to stimuli and greater spread in the brain activation once the youth go through treatment.

“So, instead of having everything focused in one area when a new stimuli comes up, and to be slow in the process of noticing this new information, it looks like they might be quicker to detect novel stimuli and appear to be using more of their brain to see this new stimuli.

“It’s our first finding that we presented at the American Psychology and Law Society in Atlanta (last spring).”

Salekin and his team will continue collecting and analyzing the EEG data, but it’s the base of the positive intervention that he hopes influences future treatment models, particularly with children.

“I think the research on this intervention is critically important because there are not many empirically-based group interventions for use in detention centers and other captive environments,” said Adam Coffey, a graduate research assistant. “And for facilities that may be short on resources, this intervention is pretty simple to implement.

“One can follow the manual and deliver the content in an engaging and excited way – you can do that for free. We’re hoping that through the research, we can disseminate it and accumulate a good evidence base for its effectiveness.”

Dr. Salekin is a researcher in UA’s College of Arts and Sciences.