TUSCALOOSA, Ala. — The worst region for flash floods in the continental United States is likely the Southwest, according to a recent analysis of flash floods by The University of Alabama.

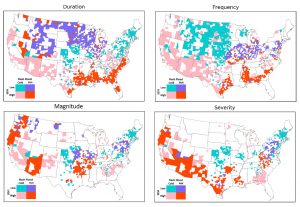

Using hydrologic data, along with socio-economic information, researchers at the UA Center for Complex Hydrosystems, led by center director Dr. Hamid Moradkhani, mapped the hotspots for flash floods.

They found the most severe effects from flash floods occur in a string of counties along the U.S.-Mexico border from Texas to California, including areas much further north in New Mexico, Arizona and even Nevada, according to the study published in Scientific Reports.

Many counties in Southwest states are not well equipped to prevent or recover from damages caused by flash floods even though the region has less frequent flash floods than other areas of the country, particularly the Southeast.

Overall, the poor socio-economic indicators in the Southern half of the U.S. affects the region’s response to flash floods events, the study found.

The Southeast states, particularly the Deep South, are hotspots for frequent and longer duration flash floods alongside poor socio-economic status, which reveals the region suffers from lack of infrastructure and sufficient resources to respond to more frequent flash flood events.

“Flash floods are among the costliest and most disastrous natural hazards worldwide because of their rapid onset that limits effective emergency response and management,” said Moradkhani. “Understanding the socioeconomic status of a region helps determine the underlying vulnerabilities, which will, in turn, be useful for discerning the risks and potential losses.”

Flash floods come from intense rainfall accumulating rapidly, and they are among the deadliest natural disasters in the world.

“The rapid onset of flash floods makes flood risk management a challenge and restricts the opportunity for timely communication and decision-making, consequently resulting in high risks of damages and casualties,” Moradkhani said.

A community’s flood risk stems from not only the intensity of rainfall and streamflow but also the people and assets exposed to potential flash floods and their lingering effects. UA researchers used a wide-range of information sources at the county level across the country.

“We analyzed the confluence of flash flood hazard and vulnerability, which can better indicate the regional risk patterns,” Moradkhani said.

The study identified the critical and non-critical regions of the country, finding the Southwest experiences severe flash flooding with a high magnitude of damage. More counties in the Southern portions of the nation are highly vulnerable to flash flood damage, while the Northern Great Plains region of the country is not a critical area.

Emergency managers and flood insurance agencies can use the data to draw resources and attention to high-risk areas ahead of expected intense rainfall, Moradkhani said.

“Our methods and tools can have immediate applications for city planning, emergency management and flood insurance, and our research can help vulnerable and disadvantaged communities to cope with adverse effect of flash floods and improve the resilience of these communities,” he said.

Along with Moradkhani, the Alton N. Scott Chair Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, the paper is co-authored by two former doctoral students of Moradkhani’s, Dr. Sepideh Khajehei and Dr. Ali Ahmadalipour, who was also a post-doctoral researcher at UA, along with Dr. Wanyun Shao, UA assistant professor of geography.

Contact

Adam Jones, UA communications, 205-348-4328, adam.jones@ua.edu

Source

Dr. Hamid Moradkhani, hmoradkhani@ua.edu