TUSCALOOSA, Ala. — By examining meteorites, research led by The University of Alabama is tackling some of the biggest questions of our solar system, chiefly how the make-up of the inner planets formed.

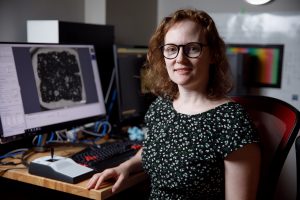

“We’re dealing with these tiny rock fragments that are so small, yet we are able to learn so much about how the planets came to be,” said Dr. Julia A. Cartwright, UA assistant professor of geological sciences.

Cartwright is leading a three-year, more than $400,000 grant from NASA to test whether meteorites from the asteroid belt reveal more about the activity of the solar system billions of years ago when asteroids and fragments of partially formed planets were shelling the inner planets, distributing metals and materials to their surfaces.

“Understanding impacts and the timing of those major events is important for understanding how surfaces came to be as they are,” Cartwright said.

About 4 billion years ago, scientists believe a change in circumstances or a major event flung asteroids and comets across the solar system, impacting the planets Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars and their satellites. Evidence for these impacts, known as the Late Heavy Bombardment or Lunar Cataclysm, comes from analysis of returned lunar materials by NASA’s astronauts from the Apollo missions or from Soviet Luna missions. The entire model of planet formation in the solar system stems from data from the moon.

“Our whole understanding of our solar system is sort of tied to an impact rate that relates to the moon, from samples of the moon,” Cartwright said. “We do not know if that event is reflected in the rest of the solar system.”

The research team will test if this event was local to the moon or widespread by examining different types of meteorites, including those from the asteroid Vesta, the second largest body in the asteroid belt. These fragments from Vesta dislodged from the surface by impacts and came to Earth over time.

Cartwright has a bank of meteorites in her lab from Vesta, which, unlike other bodies in the asteroid belt, has a structure with different layers made up of different materials, similar to Earth. She hopes subjecting these differing asteroid fragments to chemical analysis methods to determine composition and timings will show if Vesta experienced a similar bombardment as the moon or if it differed.

“I hope that I’ll be able to show that our understanding of the impact rate of the solar system shouldn’t be based solely on the moon,” she said. “If I’m finding evidence that the impact rate was actually extended, this could change those models of how planets came to be oriented as they are.”

The research can also be useful in understanding Vesta and the formation of the solar system, she said. Each meteorite is like a time capsule of information on the solar system at a certain time.

“Being able to see these different snapshots of solar system formation by looking at meteorites in the laboratory is incredible. This can be really useful with helping us to understand how our planet formed,” Cartwright said.

On this project, Cartwright and her students will collaborate with researchers at Arizona State University and the Swedish Museum of Natural History.

Contact

Adam Jones, UA communications, 205-348-4328, adam.jones@ua.edu

Source

Dr. Julia A. Cartwright, jacartwright@ua.edu