UA doctoral students provide literacy outreach in, around Tuscaloosa area

Lauren Rollins was intimidated when she enrolled in her first AP class at Tuscaloosa County High School, where she admits to being a “very average performing student.”

But her teacher, Rhonda Brinyark, recognized Rollins’ potential and “worked until I saw it, too,” Rollins said.

After graduating from TCHS, Rollins enrolled at The University of Alabama, where she earned an undergraduate and a master’s degree in education. Now, as she pursues a doctorate in special education at UA, she’s keen to replicate the influence of her K-12 teachers, including Brinyark, whom she still sees periodically around Tuscaloosa.

“It’s nice to be able to go back to these people – especially for these teachers who still need this encouragement – to come back and say, ‘you made a difference,’” Rollins said.

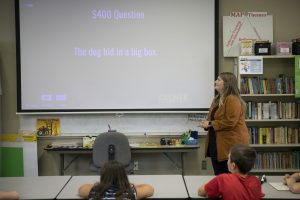

As much as Tuscaloosa has grown in recent years, it still has a “small-town feel” that continues to empower Rollins as both a leader and educator, from her three years in the classroom at University Place Elementary School, to her current role as a graduate assistant at the Belser-Parton Literacy Center at UA. Rollins and literacy center counterpart, Elizabeth Michael, operated the center’s annual summer literacy camp through the end of June.

The camp serves up to 45 children each summer and includes one-hour sessions designed for students with and without disabilities. The lessons and activities use multisensory learning strategies for phonics, vocabulary and comprehension to keep students engaged. The camp’s model and curriculum align with Rollins’ graduate research to support students with behavior needs and behavior disorders.

Both Rollins and Michael have served as graduate assistants at the Literacy Center over the last calendar year. They’ve helped run numerous literacy initiatives and teacher support projects in Tuscaloosa-area schools and in nearby Pickens County. It’s vital, Rollins said, for the center to be a hub for teachers, parents and home-schooling networks, and to make their research more meaningful for their audiences.

“The center is really leading the way in accessibility,” she said. “There’s a growing pain with that – the logistics of how that works and how it’s put into a pretty package that’s accessible for other people. But, it’s a turn toward serving our community that, as a whole, academia needs to continue.”

A family tradition

When Michael left her native Dothan to pursue an undergraduate degree at UA, her academic and professional paths had already been determined: both her mother and grandmother are UA grads and have a combined 51 years of teaching experience.

Pursuing a doctorate, though, wasn’t on her radar until she experienced learning disparities in the classroom.

She taught at Holy Spirit Catholic School in Tuscaloosa shortly after earning her bachelor’s degree in 2013 and entering the multiple abilities master’s program at UA. While pursuing her master’s, Michael began working with Jefferson County School students in kindergarten through second grade who were struggling to read on-level, and those with autism spectrum disorder.

Michael began contemplating a doctorate as she began to consider the scope of her work and the scale of her results in the classroom. A conversation with Dr. Jim Siders, former chair of the special education department at UA, helped her build the courage to leave the classroom.

“Dr. Siders told me, ‘you’re working with a small group of kids every year, and you’re impacting them,’” Michael said, “’but if you teach teachers how to do this and teach 20 teachers every year, then each of those will go out and impact a bigger group of kids.’ That really struck a nerve with me. We do need to take these strategies that we’re finding in more restrictive settings that are being useful and expand them to general education classrooms.”

Although Michael misses being in the classroom, her work with the center allows her to help both students and teachers directly and see her research inform service initiatives.

“We’re seeing our work pan out,” Michael said, “and that’s a huge motivator.”

Pickens County

Both Rollins and Michael cite the center’s work in Pickens County as the most enriching and influential of their experiences at the center.

The grant-funded “Alabama Early Literacy Project” provided materials and professional development to pre-K educators in Pickens County and gave pre-service students from UA a chance to create and implement lessons with early learners.

For Michael, the partnership was particularly fruitful for the pre-service teachers.

“To have them come back and say, ‘you were right, we can do all of this with kids in a rural environment’ summed up why we did this,” Michael said. “We saw the light bulb come on for them.”

For Rollins, her work in Pickens County provided a blueprint for how to extend UA’s resources beyond Tuscaloosa County to school systems that don’t normally reap the benefits of UA’s service networks. Rollins said UA has taught her that she “has a responsibility” to think deeply about her service and outreach to neighboring counties.

“There’s a team of researchers pouring into Pickens County – not just for education – so it’s cool to see this very holistic approach to building up a community,” Rollins said. “That’s been eye-opening for me to think about, and in the future, as it relates to service, what are our priorities and who are the people that need support?”