TUSCALOOSA, Ala. — A long-awaited, rigorous, randomized clinical trial comparing treatments for tinnitus, a perception of ringing in the ears, found no significant difference in patient outcomes between an innovative treatment and the current standard treatment.

The results, announced May 23 in JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery, come from the first definitive randomized, controlled clinical trial of Tinnitus Retraining Therapy, or TRT, a method that uses tinnitus-specific educational counseling and sound therapy to reduce the patient’s negative reaction to, and awareness of, tinnitus.

TRT was compared against the current standard of care, patient-centered counseling and current care strategies offered by the military. Both TRT and standard care encouraged patient exposure to an enriched sound environment at all times.

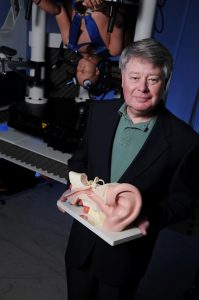

“Both treatments were effective, with one not better than the other,” said Dr. Craig Formby, a professor emeritus at The University of Alabama who led the trial. “It means there are different approaches that work. Some people will respond well to Tinnitus Retraining Therapy, and some may respond better to the patient-centered approach.”

Tinnitus is the perception of sound within the ears or head, not associated with an external sound source, most often perceived as ringing. Nearly 50 million Americans experience tinnitus, but most are not bothered by it. There is no cure for tinnitus, but there are treatments and strategies that help to relieve the associated distress and impact of tinnitus leading to improved quality of life.

Although tinnitus is often associated with hearing impairment, a recent survey estimates about 13 million people in the United States deny hearing loss but experience tinnitus. Based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates, tinnitus is severely debilitating for about 2 million people in the U.S., impairing their well-being and ability to lead a normal life. The clinical trial focused on this latter group of distressed patients.

“We know of reports of sufferers who have chronic debilitating tinnitus that is so troublesome that they elect to cut the auditory nerve to get rid of the persistent ringing,” Formby said. “However, this extreme surgical approach does not assure a cure nor relief from the tinnitus.”

Tinnitus is the leading service-related disability for U.S. military veterans, costing the Veterans Affairs medical system close to $2.5 billion annually.

The NIH-sponsored treatment trial involved 151 active-duty and retired military personnel and dependents. The trial was conducted in six Department of Defense, Navy and Air Force flagship hospitals in California, Texas, Maryland and Virginia.

The current standard of care in the military involves counseling to relieve the effects of debilitating tinnitus and forms of environmental sound enrichment to reduce the awareness of the tinnitus. The counselors typically try to help the tinnitus sufferer manage the problem by suggesting coping strategies and by providing information about tinnitus to help the sufferer control the effects of the tinnitus.

“The standard of care historically has included reassurance that the patient’s condition is not life threatening nor an indicator of imminent hearing loss,” Formby said.

In contrast, TRT is a habituation-based treatment. It assumes non-auditory brain structures, which regulate emotional and negative reactions to the tinnitus signal, are activated and give rise to the undue distress and anxiety experienced by the debilitated patient. TRT has been used for years, but it has been controversial in the absence of a definitive phase III clinical trial, which this research undertook.

The typical strategy for implementing TRT involves putting noise devices, similar in size to a hearing aid, in a patient’s ears. These sound generators emit a low-level white noise that blends with the tinnitus to reduce the contrast between the tinnitus signal and the patient’s sound background, while also resetting central auditory neuronal activity associated with the tinnitus.

The companion TRT counseling informs patients about their auditory system and explains how the ear and parts of the brain and central nervous system give rise to their debilitating tinnitus conditions. The counseling then explains how TRT leads to habituation of the effects of the tinnitus.

As part of the trial, some patients received the standard care, some TRT and some got placebo noise devices along with the counseling portion of TRT.

Patients with debilitating tinnitus lasting at least a year with mild or less hearing loss were part of the study, which included 18 months of follow-up research to monitor the effects of each treatment.

The study found tinnitus decreased significantly in all three groups with no meaningful difference in the amount of reduction among the three treatment options.

“Everybody got better regardless of the treatment they received, including the placebo sound therapy treatment with counseling,” Formby said. “Our trial findings suggest that if a patient is treated by a clinician providing quality care who listens and empathizes with the patient, then the patient will likely get better.”

Formby has been working with the U.S. military since 1999 to develop the study protocol for this pioneering investigation, which is the first definitive phase-three clinical trial of TRT sponsored by NIH. Formby’s team at UA led the scientific and clinical part of the study, funded by a $3.2 million award from the National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Researchers at Johns Hopkins University received a $2.4 million award to manage and analyze the study data.

Formby’s co-author of the paper is Dr. Roberta W. Scherer, a senior scientist at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, which served as the repository for the study results and the data coordination center for the trial.

Before retiring from UA last year, Formby was a distinguished graduate research professor in the department of communicative disorders in the College of Arts and Sciences.

Contact

Adam Jones, UA communications, 205-348-4328, adam.jones@ua.edu