TUSCALOOSA, Ala. — No mother wants to see her child hospitalized, but how she copes with it could impact the child’s anxiety level, a recent study by a University of Alabama researcher found.

As hospitals move toward family-centered care, there is a greater need to evaluate the response of the whole family, not just the patient.

By exploring the relationships between hospitalized children’s anxiety level, mothers’ use of coping strategies and mothers’ satisfaction with the hospital experience, Dr. Sherwood Burns-Nader, a child life specialist and assistant professor in UA’s College of Human Environmental Sciences’ department of human development and family studies, hoped to learn more about how the health-care team can promote coping strategies in patients and families.

“Coping patterns are important because they facilitate a person’s handling of a stressful experience,” Burns-Nader said. “If someone is going through a tough time, positive coping patterns provide extra resources that can help that person deal with the demand of a stressor.”

The study, “The relationship between mothers’ coping patterns and children’s anxiety about their hospitalization as reflected in drawings,” which was co-authored by Burns-Nader; Dr. Maria Hernandez-Reif, UA professor and director of UA’s Pediatric Development Research Lab; and CHES alumna Maggie Porter, was accepted for publication in the Journal of Child Health Care.

Burns-Nader looked at 48 mothers and children (24 mother-child pairs) who were admitted to the pediatric unit at DCH Regional Medical Center for a short period of stay. The children ranged in age from 5 to 11, with 54 percent being black and 46 percent white. The families predominantly represented the lower middle to middle socioeconomic status.

Through the use of questionnaires that looked at the mother’s coping behaviors and her satisfaction with the hospital and drawings by her hospitalized child, Burns-Nader discovered the more coping strategies a mother used, the less anxiety her child felt. In addition, when mothers used coping strategies, the more satisfied they were with the hospital experience.

“Having a child experiencing a medical illness is very distressing for parents, mothers in particular, but the child also needs a strong source of support through that process,” said Dr. Caroline Boxmeyer, a child and family psychologist and an associate professor in UA’s College of Community Health Sciences’ department of psychiatry and behavioral medicine.

“The better parents are able to manage their own stress, the more supportive and nurturing they can be for their child,” she said.

There are many coping strategies, both positive and negative, including exercising, seeking religious support, focusing on the positive, distancing one’s self, acting out, eating, drinking and more.

In this study, coping patterns were grouped into three categories: family integration (relying on family members to assist in the care of nonhospitalized children); knowledge of the hospital experience (gathering information about the child’s diagnosis); and maintaining social support (going for a walk with a friend).

“Positive coping patterns increase hope and help one feel his stress could be manageable with support found in the coping patterns,” Burns-Nader said.

Most helpful in a medical setting is for parents to have much information about their child’s medical condition so they know what to expect and can then help their child have a better understanding of what might happen during their stay, Boxmeyer said.

“That’s a really important part of the coping process for parents,” she said. “They need to have a sense of what’s coming so then they can better prepare for it. … They also need to have someone that they can talk to about their fears and their stress so when they are in their child’s presence, they can appear strong and supportive.”

In determining the child’s anxiety, Burns-Nader used children’s drawings, a technique that has long been established in clinical practice as a way to measure emotional status.

“Sometimes you cannot see how a child is thinking through their behaviors,” Burns-Nader said. “However, a drawing allows you to see their ideas, fears and concerns. It is just an insight into the child’s thoughts and anxieties.”

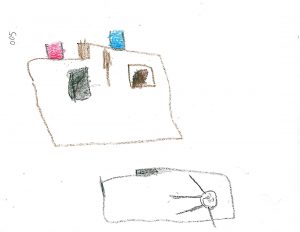

With this study, each child was given a sheet of white paper and a box of eight basic crayons and asked to draw a person in the hospital. Burns-Nader then looked at a variety of features in the drawing – facial expression, size of the person compared to his environment, presence of hospital equipment, use of colors, position of the person on the bed, omission or exaggeration of body parts — to determine the child’s anxiety level.

While this particular study looked at a small sampling of families with short hospital stays, Burns-Nader hopes to expand her research in the future by looking at how daily encounters such as out-of-pocket expenses and unexpected visitors impact the stress of parents, as well as exploring the anxiety level in children who have longer hospital stays.

Research on these relationships could provide information to health-care teams that may affect children’s care and recovery. Hospitals can help families cope with a child’s hospitalization by providing resources to the family and child such as giving information to the family, offering a family break room, supporting the hospitalized child during periods of family absence and maintaining a parent reference library.

Study findings also imply the need for interventions to familiarize children with medical procedures and equipment to decrease anxiety and to provide activities that allow children to express the sources of anxiety in an acceptable manner, Burns-Nader said. Medical teams could provide information through playroom and bedside activities or through pre-admission tours, she added.

“The medical field is utilizing family-centered care. This means we are caring for more than the illness,” she said. “The relevance of this study is that it helps us, as medical team members, see how we can care for the psychosocial needs of our patients and families. This is important because a positive psychosocial response is related to recovery and healing from illnesses.”

Contact

Kim Eaton, UA media relations, 205/348-8325 or kkeaton@ur.ua.edu

Source

Dr. Sherwood Burns-Nader, 205/348-6269, sburns@ches.ua.edu; Dr. Caroline Boxmeyer, 205/348-1325, 205/246-6087, boxmeyer@cchs.ua.edu; Traci Swann, pediatric unit nurse manager at DCH Regional Medical Center, 205/750-5176