Roman Catholics and other Christians living in China today face a dilemma, says Dr. Anthony E. Clark, assistant professor of history at The University of Alabama. Changes in the communist state’s attitudes toward religion have allowed many Catholics to live in the open, but they live in terror – their freedom may be removed at any moment.

“You see this enormous restoration work on churches and this enormous freedom given to Protestants and Catholics,” says Clark, who teaches Chinese history and culture at UA. “Yet at the same time, you’ll see an arrest of an underground bishop, or a couple gets a warning from the party police about a visit they had with a foreigner. So the old powers are still there, and you don’t know when they will re-emerge. Chinese Christians are enjoying a freedom that causes an equal amount of anxiety. They’re terrified. They live in terror for the freedom that they have.”

Clark, who is a Catholic himself, returned in December 2008 from a semester studying the history of Christianity in China, particularly the stories of Roman Catholic martyrs and the destruction of Christian churches during the Boxer Rebellion from 1898 to 1900. He has been blogging about his experiences on the Ignatius Insight Web site. On the site, he discusses how the packed Catholic churches in Beijing reflect the growing numbers of Chinese citizens professing Christianity.

“Before the communist revolution, Christianity was a tiny little minority, and it’s still a minority, but it’s the fastest growing religion in China today,” Clark says. “Catholics were three-fourths of Chinese Christians, and Protestants one-fourth before the revolution; today it’s the opposite. Protestants are three-fourths of the Catholics in China, and Catholics are one-fourth. The Protestant house churches are exploding. There are so many.”

During his travels, he met with Roman Catholic priests, nuns and lay persons in several provinces. Since the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and ’70s, when almost all Christian churches in China were wiped out, the Roman Catholic Church has been rebuilding. A new openness emerged in the early 1980s during the regime of Deng Xiaoping.

“During the years of closure, from the 1950s to early ’80s, some of the priests were dairy farmers or had regular jobs and would carry out their priestly duties at night,” says Clark, who is finishing a book about Catholic martyrs in China. “They kept in closed communities. One bishop said to me, in the 1960s and ’70s you didn’t even know who a Catholic was. They led private lives. You couldn’t see one from the next. Then when the churches reopened in the ’80s, suddenly you knew, wow, my neighbor is a Catholic.”

The Chinese government, however, discouraged links between Chinese Catholics and the worldwide Roman Catholic Church. The Roman Catholic Church was perceived as a foreign power, and the Communist Party did not want Chinese citizens to be subject to a foreign authority such as the pope. So the government formed the Patriotic Catholic Association, in which the Communist Party began to appoint bishops. The association professed no relationship to the Vatican. Meanwhile, underground bishops who had clandestine ties to the Vatican led a “secret” church. Both aboveground and underground bishops ordained priests. But, since the late 1990s the two churches have begun merging.

“It used to be all patriotic bishops were disconnected with the Vatican,” Clark says. “At this moment, about 98 to 99 percent are what we’d call openly in communion with Rome, which means that there are probably only two or three bishops left in China who are not in open communion with the Vatican. The new complicated situation is that the so-called underground bishops literally live with or share the same building with the so-called patriotic bishops.”

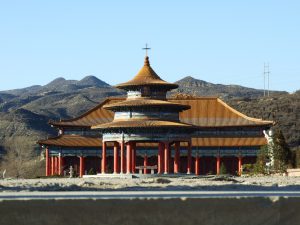

In his extensive travels throughout northern and central China, Clark saw many contradictions in how the Chinese government and the Communist Party treated Christians. For example, in Guizhou Province, Clark found an “underground” bishop who was allowed to live in the cathedral but had to keep his ring in his pocket while two “aboveground” bishops, who were working with the Communist Party, flourished in Kunming with chauffeure-driven cars. On the other hand, in Shanxi Province in northern China, Christian churches have gained tremendous influence.

“Every area in China is different,” Clark says. “The bishops say if you’ve been to one region, you’ve been to one region, and the region next door can be a totally different story . . . . If you go to Shanxi province, the Christians are more powerful than the government. There is one area in China where, literally speaking, the church and the party headquarters are across the street from one another, and the party has less power than the church. The Chinese government just throws its hands up and says, ‘well, we just have to let it go – as long as they’re good.'”

Still, Catholic Christians face many possible pitfalls in China, Clark says. For example, although books about the history of Christianity in China and Roman Catholic materials are available in churches and bookstores, Internet access to information on Pope Benedict XVI is often cut off, and photos of him are rare. Also, a couple who helped Clark and his wife in his travels were visited by party police.

“I got an e-mail later saying that the local party police had approached their church and had expressed to this couple that they knew everything that they did with the two foreigners, and that they were being watched,” Clark says. “They were terrified. So the claws are still out.”

In addition to contemporary church issues, Clark’s research reaches back into a period of violent repression of Christianity during China’s Boxer Rebellion, a backlash against Western influences that lasted from about 1898 to 1900. Clark visited Christian villages that anti-foreigner and anti-Christian rebels attacked and found stories, writings and tablets that recounted massacres and commemorated the victims. Clark uncovered several items and writings hidden during the 1960s and ’70s during the Cultural Revolution.

“What I basically discovered were several of these stone tablets and paintings of churches that were destroyed during the boxer uprising that were hidden during the Cultural Revolution,” he says. “I collected a number of oral testimonies. So basically what I’ve been working on is trying to uncover ecclesial sources and accounts of what happened on the grass-roots level during the rebellion. I was talking to the families of the people who were there rather than consulting archival records, which can provide a rather biased, or incomplete, picture.”

What Clark found was that, contrary to many secular accounts of the Boxer Rebellion, the violence was mostly focused on Christians rather than political agents.

“When the Boxers were attacking a certain village, say a Protestant village, they would say, ‘do you apostatize,'” Clark says. “‘Will you renounce your faith?’ If they did, they were released. If they didn’t, of course, they were killed. That removes a purely political motive. Even French missionaries were released as long as they renounced their religious affiliation. Very few did, and the Chinese who apostatize were certainly released. So, it was a far more religious event than people realize.”