Fossilized Discovery Leads UA Paleontologist to Find Early Whales Used Back Legs for Swimming

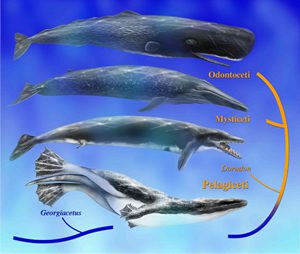

The crashing of the enormous fluked tail on the surface of the ocean is a “calling card” of modern whales. Living whales have no back legs, and their front legs take the form of flippers that allow them to steer. Their special tails provide the powerful thrust necessary to move their huge bulk.

Yet, this has not always been the case. Reported in September in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Dr. Mark D. Uhen, a paleontologist of the Alabama Museum of Natural History at The University of Alabama, describes new fossils from sites near Coffeeville in southwestern Alabama and Newton in southeastern Mississippi that pinpoint where tail flukes developed in the evolution of whales. “We know that the earliest whales were four-footed, semi-aquatic animals, and we knew that some later early whales had tail flukes, but we didn’t know exactly when the flukes first arose,” Uhen says. “Now we do.”

The most complete fossil described in the study is a species called Georgiacetus vogtlensis. Although not new to science, the new fossils provide new information. In particular, previously unknown bones from the tail show that it lacked tail flukes. On the other hand, it did have large back feet, and Uhen suggests that it used them like modern whales use their tail flukes.

Undulating, or moving the body in a wave-like fashion, was a key factor in the evolution of swimming. “When whales move their flukes through the water, it creates a force to move them forward,” Uhen says. “Georgiacetus is doing something similar with its feet.” The different body forms seen in the lineage of whales point to different methods of swimming underwater.

Previous studies have proposed a possible process to evolve from the ancestral form, paddling with all four legs, to the modern-day whale in which the tail oscillates up and down. Living vertebrates that are capable swimmers employ a whole range of different techniques, including five particularly well-defined methods: quadrupedal paddling, paddling only using the back legs, undulation of the hips, tail undulation, and tail oscillation. Interestingly, it had been suggested that during whale evolution that each of these steps occurred in turn, but that the hip undulation stage might have been by-passed.

The discoveries indicate that the complete opposite was true, and as Uhen says, “wiggling hips were a significant step in the evolution of underwater swimming in whales.” Uhen’s current work includes research on the relationship of whale diversity and global climate change, the origins of modern whales and field work in the Southeastern United States, the Pacific Northwest and the coast of Peru.

Appointed to the Alabama Museum of Natural History in June, Uhen is also an adjunct research scientist at the University of Michigan Museum of Paleontology, a research associate of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County and a research associate at the United States National Museum of Natural History.

Further Reading