Engineering Student Investigates Hybrid Hype

By Chris Bryant

As gas prices hover near the $3 a gallon mark, drivers are tempted to try and squeeze every inch of travel possible from each drop of gasoline.

Gasoline-electric hybrid vehicles are touted for their fuel efficiency and environmental friendliness. However, some motorists have expressed frustration with the hybrid hype, claiming the vehicles don’t live up to the EPA mileage estimates plastered on their window stickers.

Do they? If not, how much do they fall short and, how much of a factor does speed play in any shortcomings? One University of Alabama mechanical engineering graduate student, Courtney Jenkins-Lindwurm, decided to find out.

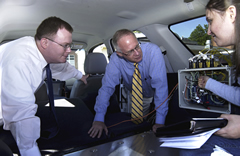

For her master’s thesis, Jenkins-Lindwurm decided to test the fuel efficiency of a 2005 Ford Escape Hybrid. Through a partnership UA has with Argonne National Laboratory, Jenkins-Lindwurm earlier traveled to Chicago where, working alongside Argonne researchers, she equipped the vehicle with a data acquisition system. Linked to a laptop inside the vehicle’s interior, as well as to a removable compact Flash card, the system measures and stores multiple performance factors under various driving conditions.

Throughout the spring semester, Jenkins-Lindwurm put the hybrid, as well as a conventional 2003 Ford Escape, through a variety of mileage tests on both the open highway and in city traffic. Her results?

Driving 5-10 miles per hour above the speed limit had a greater negative impact on the hybrid’s gas mileage than such “fast” driving did on the conventional vehicle, the UA engineering student said.

“Basically, I did find that with the conventional it was plus or minus five (miles per gallon),” Jenkins-Lindwurm said. “With the hybrid, in the city, it got 10 (miles per gallon) under, at worst.”

The hybrid achieved or exceeded the EPA mileage estimates for the highway when driven at or below the speed limit. During city driving, the hybrid achieved the mileage estimates only when sustaining speeds 5-10 miles per hour slower than the speed limit.

What should one make of the results? “My advice is to slow down,” Jenkins-Lindwurm said, regardless of whether you drive a hybrid or a conventional vehicle. “If you just slow down and take those extra couple of minutes, you can save yourself a lot of extra money in the long run.”

Besides, driving 5-10 miles per hour faster over the test courses’ 7-10 mile routes made little difference in how quickly the UA student arrived at her destination. “The difference in time between the slow and fast was only about three minutes.”

Dr. Clark Midkiff, associate professor of mechanical engineering and director of UA’s Center for Advanced Vehicle Technologies, said the experience Jenkins-Lindwurm, and future UA engineering students, receive from such projects is invaluable.

“Our students are getting in on the ground floor of what we anticipate to be an exciting and rapidly growing technology,” Midkiff said. This study is one of several made possible through an approximate $1-million Department of Transportation research grant awarded the Center, some $400,000 of which is earmarked for hybrid related research. Each project is aimed at improving hybrid electric vehicle performance and fuel economy.

Research results from the Ford Hybrid Escape partnership with Argonne will be used to validate simulations of hybrid technology developed at UA.

“The CAVT is also working to improve regenerative braking so that more energy captured during braking can be returned to charge the battery,” Midkiff said. Another study is aimed at optimizing the control and performance of the internal combustion engines used in hybrid systems, he said. In that project, UA researchers are exploring options in sending power to either the electric generator or the driveshaft.

Principal investigators on the Center’s hybrid-related research, in addition to Midkiff, include Drs. Keith Williams, Tim Haskew and Paul Puzinauskas.

The global demand for hybrids presently exceeds the supply, Midkiff said, keeping prices artificially elevated. As more manufacturers enter the hybrid game and others increase the number of models available, prices will likely fall, while hybrid performances simultaneously improve, he said.

That’s improvement in a performance that, according to Jenkins-Lindwurm is already adequate. “Their goal was to have their hybrid have a V-6 like performance,” the UA graduate student said of Ford Motor Co.’s development of the Escape hybrid. “They wanted to make sure it had the same performance value as the conventional Escape.” In the graduate student’s eyes, they succeeded. “I really didn’t see a big difference between the two.”

Further Reading