Since 1967 Jungle Discovery Anthropologist Has Been at Forefront of Olmec Research

by Chris Bryant

Considering Dr. Richard A. “Dick” Diehl was born in Bethlehem, perhaps it’s no wonder much of his life’s work has focused on the birth of an ancient civilization.

Diehl’s birthplace was the Pennsylvanian city, rather than the Palestinian one referred to as the cradle of Biblical history, and his professional career has focused on some of the peoples, including the Olmecs, who once inhabited parts of Mexico.

Believed to be the creators of the first civilization in Mesoamerica (which includes much of Mexico and Central America), the Olmecs have been linked with Diehl for some 40 years. In 1967, while working as a field director on a Yale University archaeological project in the jungles of San Lorenzo, Mexico, the budding anthropologist assisted in an astonishing discovery – one in which other researchers have continuously expanded – which still reverberates today.

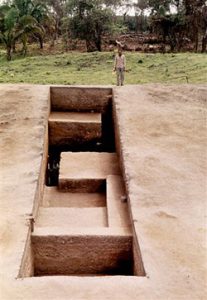

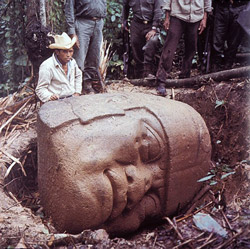

“We had seen a monument sticking above ground,” Diehl recalled of the events from four decades ago at the now famous Olmec site. “I went out to expose it, and we had to cut down trees and clear the area. As I started excavating the monument, which was just a plain stone slab, I expanded the excavation and hit another stone monument. We cleared the area, and it turned out there were several lines of monuments.”

In all, the group discovered 13 monuments at the site. Diehl was personally involved in the recovery of one colossal stone head, which weighed approximately 10 tons, and seven or eight other monuments from the area, located atop a plateau.

“It was quite thrilling,” Diehl recalled. He said he remembers thinking, “‘So, this is what it’s like to be an archaeologist.’” He only later learned just how rare such discoveries are. “I never found that much stuff in my life again,” the UA anthropology professor said.

More important, anthropologically, than the monuments themselves, was that the group Diehl was working with was able to date the abandonment of the monuments.

“That had been a big issue in Olmec studies,” Diehl said. Through carbon dating and other techniques, the group confirmed the stones were abandoned about 900 B.C., “which was quite a bit older than most people thought the monuments were.” Since that time, through more discoveries and more sophisticated testing techniques, anthropologists now place other Olmec artifacts from the site at about 1500 B.C.

At the time, the anthropologists thought the monuments – some of which weighed about 20 tons and were carved from stones brought from some 60 miles away – had been deliberately buried. They now know better.

“This was actually a workshop, a place where they were bringing in existing monuments, were breaking them and carving smaller monuments out of them,” Diehl said.

At its height, the site where the then 26-year-old Diehl uncovered first one monument, then another and another, was part of an archaeological site that was once, at its peak, part of the largest community anywhere in the Americas. “It’s about seven times bigger than we thought it was,” Diehl said. “The whole sides of the plateau are also part of the archaeological site. We cut the jungle down on the plateau top – that took us two years, with about 50 guys with machetes, cutting it down, burning it off and mapping it. But the jungle on the sides of the plateau was much denser than the jungle on top.” So, that area was inadvertently left for future discovery.

If Diehl wasn’t already convinced that the Olmecs were worthy of significant study, playing such a central role in a breathtakingly important discovery did so. A significant portion of his career since 1967 has been devoted to the study of the Olmec culture, and he is widely considered one of the world’s leading Olmec experts. He’s lived in San Lorenzo for a total of 12 months, during two separate field seasons, and he’s traveled back to the area for study on 10 different occasions.

Diehl’s 2004 book, “The Olmecs: America’s First Civilization” was published to widespread acclaim, with reviewers in American Archaeology referring to it as “a must for students of ancient Mesoamerica.”

As more information about the Olmecs – which scientists only first learned of in the 1940s – became known, discussions about the degree of this people’s influence on their contemporaries became more heated among scientists. Those discussions have, in some cases, become arguments. And those opposing views aren’t voiced only in the scientific community, but are now playing out in the largest of mainstream media outlets.

Earlier this year, The New York Times, in a lengthy section front feature, weighed in on the debate, quoting Diehl frequently and prominently in a story focusing on the differing views of Olmec influence – the so-called Mother vs. Sister Culture argument. In its extreme forms, supporters of the Mother Culture believe the Olmecs’ influence was great and wide, and through extensive trading and other means gave birth to similar cultures throughout the region. Those supporting the Sister Culture view argue that the Olmecs shared their ideas with other cultures and vice versa, leading to a blending of cultures, where distinct peoples share similar views and styles of politics, religion and arts.

The argument was most recently rekindled in February 2005 in Science magazine, with Diehl – who falls closer to those supporting the Mother Culture theory – being invited to author a reaction piece to results from pottery experiments supporting the Mother Culture theory. “I think it’s pretty evident the Olmecs had a much greater influence on their neighbors then their neighbors did on them,” said the UA College of Arts and Sciences researcher.

He has also served as a scientific adviser to NOVA, the PBS science television program, in an extensive episode on the Olmecs, in which the producers attempted to analyze how the historic people might have transported and carved the massive monuments for which they are known. And Diehl was one of four scholars who selected the pieces of Olmec art to be transported from Mexico for an exhibit he co-coordinated at the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. in 1996.

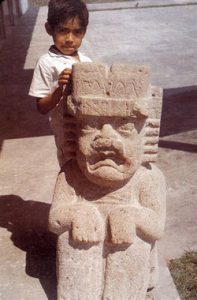

While much is known about the people the Aztecs first called the Olmecs, literally “rubber people,” much remains unknown, including what the people called themselves.

“We don’t have any burials,” Diehl said, “I think because, frankly, we’re digging in the wrong places. They are probably buried beneath house floors, and we’ve been concentrating on big public buildings. We do have ceramic figurines, and some of these sculptures are likely fairly realistic. What they tell us, at least, is that these people were very short and stocky with broad faces, sort of round headed, much like many of the people who are in the area today and who are, in many ways, the descendants of the Olmecs.” Their skin tones, researchers believe, would have been similar to today’s Native Americans.

“They lived in a variety of different kinds of settlements, some as high as six to seven thousand people.” Others lived in much smaller villages. Most of the people were farmers, growing crops such as maize, beans, squash and sunflower seeds.

“We know they hunted deer and ate dog, as all ancient people did,” Diehl said. They also consumed fish and other aquatic resources. “They had a pretty rich subsistence. Most of the people were day to day farmers; a few were rulers, merchants or priests. We do not have any evidence of professional warriors, but I’m certain warfare was carried out. It probably just involved everybody.”

There is evidence, Diehl, says of social stratification. “Some people had jade jewelry and elaborate costumes – the rulers did and their families, the priests – these are not things the ordinary person would have worn.”

Their exact language is unknown although researchers think they know to which family of language it likely belonged. Scientists recently confirmed the Olmecs also wrote their language.

Considering the Olmecs existence was only discovered some 60 years ago, much is known about the people and their lives. But Diehl says what he would most like to know about the people he’s studied for nearly 40 years, will likely never be known, even if those elusive burial sites are one day discovered.

“I would like to know what an Olmec ruler’s thought process was over a 24-hour day,” Diehl said. “Did they have as much trouble ruling their people as I did running a department? What were their goals, their aspirations? For all our differences, what are the things that we share?”

Further Reading